Gordon Waddell, back pain, the subversion of the biopsychosocial model, and the UK government's development of a victim-blaming approach to disability.

This story begins innocently enough: Gordon Waddell was a Scottish orthopaedic surgeon who revolutionised the treatment of lower back pain.

Lower back pain is a very common problem. Because it can strike people who are quite young and is often chronic or remitting, it has a profound impact on many people’s lives. To put it in terms that people who only care about work and money can understand: it brings high rates of healthcare utilisation, high rates of absence from work, and high rates of presenteeism (being less effective at work). It’s the number one disorder in years of disability.

In the 1980s and 90s people who developed serious lower back pain were advised by doctors to take two weeks’ full bedrest. However Waddell argued that these patients shouldn’t take bedrest; instead, they should stay active and return to their normal activities as soon as possible. Today, this is the standard advice for people with lower back pain. Research shows pretty clearly that staying active does indeed bring better outcomes than bedrest for people with new-onset lower back pain, and those with chronic back pain benefit from exercise therapy and intensive rehabilitation.

So far so good. But you have to know I wouldn’t have written about this unless there was some juicy scientific scandal to explore, and there is. It involves the biopsychosocial model.

The biopsychosocial model of medicine was introduced by the internal medicine doctor and psychiatrist George Engel in 1977. Engel argued that it isn’t enough for doctors to be experts in biological medicine, they must also understand psychological and social factors that affect their patients, and they must deal with patients holistically, that is, they must see the patient as a whole person, not just as a collection of symptoms, signs and diagnoses.

In the decades following its introduction the biopsychosocial model became ever more widely accepted in medicine. Medical students are taught that it should form the basis of their practice. It is seen as compassionate, holistic and humanistic, and I think most doctors would be shocked to hear anyone criticise it.

Although in theory the biopsychosocial model applies to all areas of medicine, in practice it’s most often talked about in the context of mental health conditions. No-one talks about the BPS model when they’re discussing how to set a broken bone, or how to provide the correct antibiotics for a bacterial infection. It is most often discussed in the context of complex mental health problems such as addiction or depression.

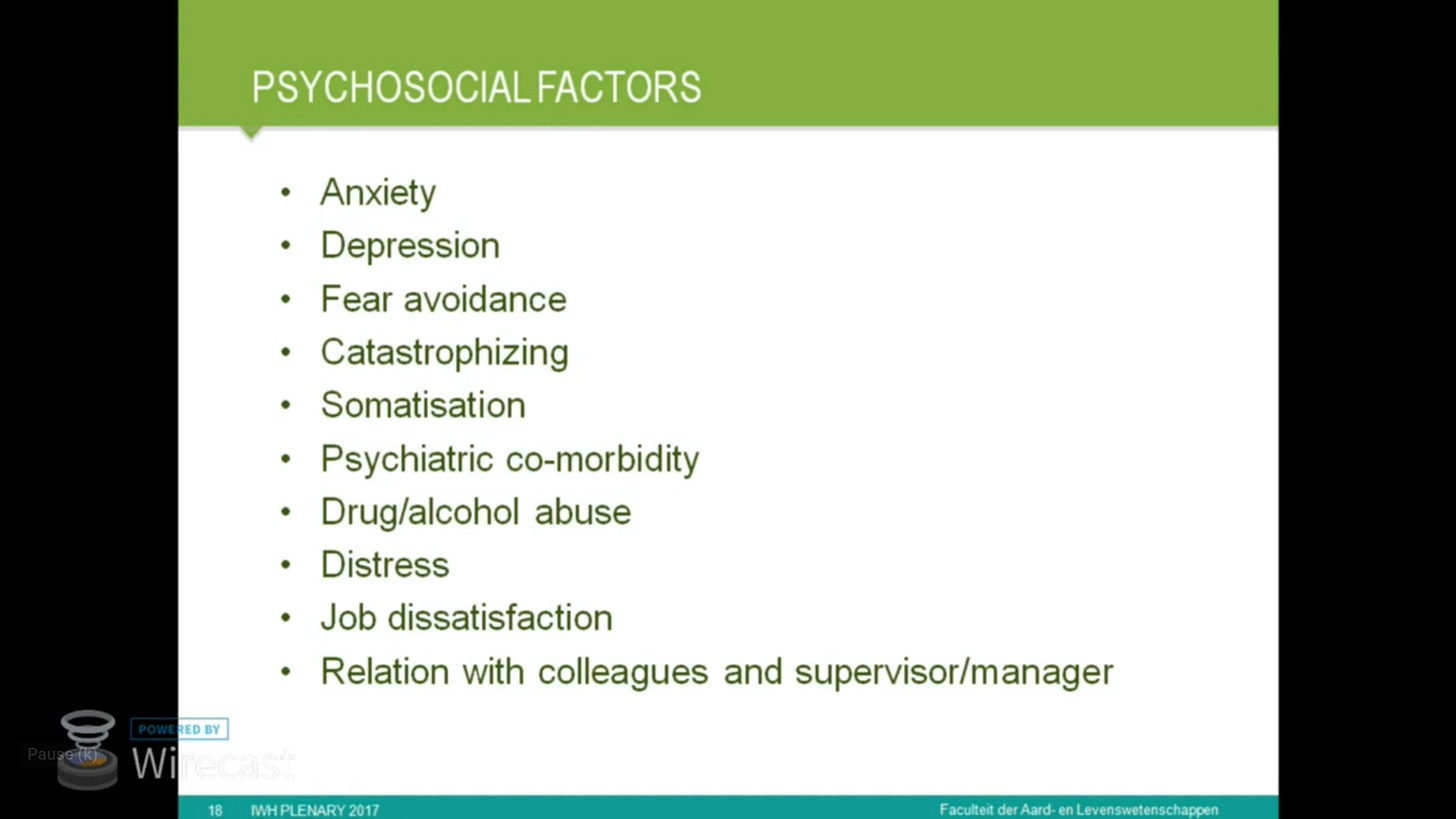

In his 1987 paper A new clinical model for the treatment of low-back pain, Waddell introduced something new: a biopsychosocial model of back pain. In it, he claimed that back pain can be caused by psychological and social factors. According to Waddell, a person can develop back pain because they are depressed or anxious, or because they are unhappy at work. He partly blamed the rise in back pain-related disability on doctors who coddle their patients; according to Waddell, people remain sick and disabled because their doctors tell them they are. He argued that it is important to distinguish ‘nominal’ from ‘substantive’ diagnoses; in ordinary language, this is the idea that some people are really sick (substantive), but others are not really sick at all (nominal). This is similar to the idea in UK government policy that there are deserving and underserving poor; an idea which is used to justify denying state benefits to those who are deemed ‘undeserving’. In Waddell’s view, most disability due to back pain is nominal; these patients should be expected to return to work, and should not be allowed long-term disability benefits.

Waddell further developed these ideas in his 1998 book ‘Back Pain Revolution’. In this book the patient’s social environment, “illness behaviour”, psychological distress, and attitudes and beliefs all contribute to pain and disability.

A new version of the biopsychosocial model

Waddell’s biopsychosocial model of back pain was revolutionary. (I don’t mean that in a good way). Although the biopsychosocial model was well-established by this point, the idea that social and psychological factors could partly or wholly cause a physical condition, such as back pain, was new. (Or rather, it was old, but people don’t like to use the word ‘hysteria’ anymore. Attaching the idea that physical illness could be ‘all in the mind’ to the BPS model was new). Waddell’s ideas are often described as flowing naturally from Engels’ original model, but in fact they were a radical departure from it.

Partly because Waddell was right about exercise being good for back pain, and partly because of his clever adoption of the popular ‘biopsychosocial model’ brand, Waddell’s ideas gained popularity and came to be accepted as ‘truth’. However, the evidence points in another direction. As of 2017, systematic reviews have failed to find good-quality evidence that Waddell’s psychosocial factors contribute to back pain.

“If you look at the associations between psychosocial factors and back pain then the associations are weak… and if you look at the interventions that target on these psychosocial factors then the effects are small also. It's a little bit disappointing after twenty-five years of the biopsychosocial model.”

- Dr. Maurits Van Tulder, back pain expert and member of Cochrane’s Back and Neck group

Despite what the evidence says, I suspect many doctors and other clinicians still cling to the false belief that their patients with lower back pain are just neurotic or don’t like their jobs.

Waddell’s work with the UK government on disability benefits policy

From 2005 to 2010 Waddell contributed to the Labour Government’s Health, Work and Wellbeing Strategy.

Waddell worked with Mansell Aylward at the UNUM-sponsored Centre for Psychosocial and Disability Research. This centre worked extensively with the UK government’s Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). An important publication was Models of Sickness and Disability: Applied to Common Health Problems, by Waddell and Aylward. In it, the authors claim that it is rare for a person to have genuine long-term disability. According to the authors, most people who are disabled can return to work, and if a person fails to return to work it is, essentially, their own fault. This victim-blaming mentality continues to underpin UK government policy towards disabled people.

Notes

In 2003 Waddell received a CBE (Commander of the British Empire) award.

Epilogue: the Waddell signs

In a 1980 paper Nonorganic physical signs in low-back pain, Waddell described eight clinical signs which, in his view, point to pain being non-organic, that is to say, either faked or imagined. For example, there’s one test where the clinician pushes on the top of the patient’s head - this doesn’t actually put any pressure on the spine, so if the patient says it hurts, this is interpreted to mean the pain is ‘non-organic’ - either fake or imagined. These signs are demonstrated by physiotherapists in the video Is Someone Faking Back Pain? How to Tell. Waddell's Signs - Tests.

I have so many problems with these signs.

It is unethical for a clinician to lie to a patient, except in very extreme circumstances where the patient is in danger. Yet in order to look for Waddell signs the clinician must deceive the patient; the clinician pretends she is looking for signs of back pain, when in reality she is looking for signs that the back pain is faked or imagined.

Patients are often fearful that a clinician will not believe them. Patients often feel they have to ‘perform’ their pain in a way the clinician will find acceptable. I can very easily imagine that when a clinician performs a Waddell test the patient might think: “I don’t really feel anything, but obviously I’m supposed to feel something, maybe the doctor is doing it wrong, I’d better say it hurts.”

I don’t believe these signs are as objective as they pretend to be. It’s very easy for a clinician to, consciously or unconsciously, influence the patient. Suppose while checking for a Waddell sign, the clinician looks impatiently at the patient and says: “well?” This would be an obvious cue for the patient to say they feel pain, whether they actually do or not. Suppose a racist clinician is dealing with a patient who they dislike because of prejudice. It would be easy for this clinician to cue the patient to give the wrong answer. This might not even be deliberate; the clinician might be unaware of her subconscious desire to ‘prove’ the patient’s pain is faked or imagined.

References

Shakespeare, T., Watson, N., & Alghaib, O. A. (2017). Blaming the victim, all over again: Waddell and Aylward’s biopsychosocial (BPS) model of disability. Critical Social Policy, 37(1), 22-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018316649120

The biopsychosocial model: Time for a new back pain revolution? (May 2, 2017): Back pain expert and Cochrane Back and Neck Group member Dr. Maurits Van Tulder discusses the last three decades of research and clinical practice.

Is Someone Faking Back Pain? How to Tell. Waddell's Signs - Tests: Two US physiotherapists demonstrate how they check for Waddell’s signs.

Waddell G. 1987 Volvo award in clinical sciences. A new clinical model for the treatment of low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1987 Sep;12(7):632-44. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198709000-00002. PMID: 2961080.

Waddell G, Aylward M (2010) Models of Sickness and Disability: Applied to Common Health Problems. London: Royal Society of Medicine.

Obituary - Gordon Waddell, surgeon who transformed the treatment of back pain. 9 May 2017, The Herald.

Couldn't agree more, as it has resulted in much gaslighting of those of us with diagnosed chronic secondary low back pain issues. We are referred to as a "minority" within the demographic of chronic LBP, yet ALL treatments seem overly focused on the psycho-social aspects now, which will only help the majority of people who have chronic primary low back pain imho [i.e. no "tissue damage" etc].

Excellent. A must read.