Mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS): what it is, how to tell if you have it, and how to treat it (with or without a doctor's help)

MCAS is so medically neglected, it makes ME/CFS look mainstream. But there are ways to manage and treat it.

I’m not a medical professional and this post is just for general information, not medical advice. I’m doing my best to be accurate, but this is a topic that I’m still learning about myself. If you have MCAS I hope you have a knowledgeable and supportive doctor to help you find the best treatments, but I know this isn’t available to many of us. I’ll link to information about MCAS provided by medical professionals at the end of this post.

What’s MCAS?

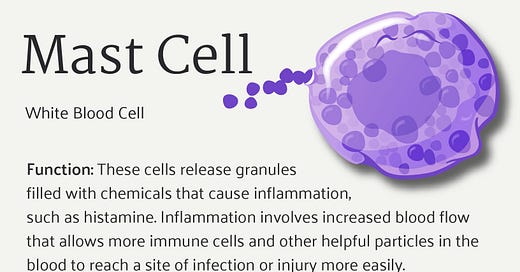

Mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) occurs when a type of immune system cell called a mast cell becomes over-active and releases chemicals, including histamine, which make you sick. Mast cells are also known for causing allergies, but MCAS is not the same as allergies. However, medications which are intended to treat allergies can also be used to treat MCAS.

MCAS is common, and people who have ME/CFS, long Covid, POTS or fibromyalgia often have MCAS as well. However in the medical world MCAS is mostly not recognized, and there is little research about it. The knowledge that we do have about MCAS mostly comes from doctors who specialise in treating ME/CFS or long Covid, who have learned through experience and through trial and error.

What are the symptoms of MCAS, and how can you tell if you have it?

For me, the main symptom is that you get very sick 30-40 minutes after eating food. This can be severe and debilitating. For some people, MCAS makes it very difficult to get enough nutrition. People also sometimes get various types of rashes, gastrointestinal symptoms, and a long list of other symptoms.

MCAS symptoms tend to come and go, they aren’t just ‘on’ all the time. The symptoms usually have a trigger; it could be heat, cold, food, or something else. If you have ME/CFS, post-exertional malaise can trigger MCAS.

Practically speaking, the way to tell if you have MCAS is to try antihistamines or other medications that target mast cells and/or the chemicals they release. If your symptoms improve with these medications, then it’s MCAS.

Managing MCAS through diet

It can help not to eat much food at a time. Say goodbye to eating meals, and say hello to having three bites of food every 90 minutes throughout the day.

Beyond that, there are three diets that some people find helpful:

gluten-free diet

histamine diet

low-FODMAP

This website has info on a histamine diet.

Some people find it makes more sense to simply look for ‘safe’ foods they can eat, rather than looking at a particular diet.

What over the counter medications can you take for MCAS?

I’m currently taking:

• Fexofenadine (Allegra) 360 mg per day. This is a non-sedating H1 anti-histamine. There are several alternatives you could use instead, such as Claritin or Aerius.

• Famotidine (Pepcid) 80mg per day. It’s a histamine H2 blocker that also works as an antacid.

• Benadryl at night at the recommended dose. Benadryl contains a sedating antihistamine. (Note that Benadryl is sold all over the world, but it contains different ingredients in different countries. The Benadryl outside Canada and the US might not be right for people with MCAS, I’m not sure.) It’s worth considering that there’s some evidence long-term use of Benadryl could cause dementia.

I chose these medications partly based on a video by Dr Ric Arseneau about MCAS. The video is long but the part about medications starts about 44 minutes in. In the video he refers to a treatment protocol which you can find at this link.

If you want to try these meds, it’s best to try them one at a time, and start at a low dose. Note that while these are over-the-counter meds, some of the dosages I listed are higher than the recommended dose. If you do take these and find they work, you should see if you can taper down the dosage - if you get the same effect with a lower dose, so much the better.

For some people, it might make sense to get these meds on prescription even though they are available over-the-counter, because it might work out cheaper.

There are also prescription medications you can take for MCAS if the over-the-counter ones aren’t enough. However it can be difficult to find a doctor who will prescribe them.

MCAS is medically misunderstood, and tends to get confused with another condition, mastocytosis

Even though MCAS is common, most doctors have never heard the term ‘mast cell activation syndrome’. However they have heard of mastocytosis, a rare and very serious disease in which mast cells function abnormally. MCAS and mastocytosis are two separate conditions. But if you say to a GP that you have mast cell activation syndrome, the doctor will most likely think you mean mastocytosis. And since mastocytosis is rare and an odd thing for a patient to self-diagnose with, the GP might conclude that you are a hypochondriac, or just a bit crazy.

Even if the GP agrees with you that you might have MCAS, things will still go horribly wrong. The GP, having no idea how to treat an MCAS patient, will treat you the same way they would treat a mastocytosis patient. They will send you to the wrong specialist - an immunologist - who will do the wrong tests. These tests will most likely come back negative, and the immunologist will conclude that there is nothing wrong with you.

When should you talk to your doctor about MCAS?

Sadly, I don't think you should ever talk about MCAS with your GP, or (almost) any other doctor. The GP will not understand what MCAS is. (This is true even if the GP is pretty good about ME/CFS or long Covid - MCAS is so medically unknown, it makes ME/CFS look mainstream by comparison.) There is a danger the GP could decide you’re crazy or foolish or a hypochondriac, and could write something on your file which makes it harder for you to get medical care in the future.

This is all incredibly unfair and wrong and I'm so sorry.

The only exception is if you are lucky enough to be able to see a doctor who is a specialist in ME/CFS or long Covid, one of the ‘good ones’ who is trusted by patients. These doctors will have seen MCAS many times before in their other patients, so they will understand, and they will be able to offer treatments that can help.

If you are trying to convince a GP to give you a referral to an ME/CFS or long Covid specialist, definitely DO NOT talk about MCAS. Just talk about your ME/CFS or long Covid symptoms. Once you get to the specialist, then you can talk about MCAS.

Never go to an immunologist about MCAS. They will look for mastocytosis, and when they don’t find it they will say there’s nothing wrong with you.

Mast cells and their mediators are hard to study, and therefore we know comparatively little about them

Mast cells are hard to work with in the lab because you have to keep them cold the whole time. Ideally the nurse or lab worker should take the patient’s blood using a chilled syringe, put the blood in an ice box, centrifuge it in a (very expensive, not widely available) chilled centrifuge, put the plasma immediately in the freezer, and do any lab work using chilled equipment. This makes everything much harder and more expensive. It also means that a negative result is hard to trust - is it negative because there’s really nothing there, or because the lab worker just didn’t get the test tube into the fridge fast enough?

My MCAS experience

I started to find that I’d get deathly ill 30-40 minutes after eating - all I could do was lie in bed for hours and wait for it to pass. Cutting out certain foods helped a lot; I cut out gluten, alcohol, sugar, and all carbohydrates or starchy foods (so basically all the things I used to enjoy!) I switched to eating only a small amount of food at a time and this also helped, but it didn’t entirely solve the problem. I was losing weight - when you get very sick every time you eat, you end up not eating much. It was scary. I eventually saw a wonderful specialist doctor who prescribed some medications that made the symptoms a great deal milder. The symptoms are still pretty bad, but at least I’m no longer worried about not being able to get enough nutrition. I later found out that these medications are also available over the counter.

More information

• Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS) - Bateman Horne Center - 50 min talk aimed at clinicians. The section on treatments begins at around 20:50.

• Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS) - METV - Dr Ric Arseneau - 90 min talk aimed at patients. There’s a lot of information but I found that it isn’t particularly clear or easy to follow. The section on treatments begins at around 40:00.

• Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS) - Dr Todd Madeiris - webpage, contains detailed information on a low-histamine diet.

I have been dealing with this since the 90s. Most difficult symptom is hives. At one point I was under 100 pounds (5'4"). I found Zyrtec nightly works best for me. Namebrand works better so I can usually use 1/2 tab.

Cimetidine is next step when zyrtec not enough. But last time I needed it the side effect of hard swollen glands became too serious to continue. It's a rare side effect...

Avoiding food triggers is still my main tool. It took a food/symptom diary to track down the things that are the worst culprits. A diet that rotates foods (nothing repeated within 4 days) also helps.

Wheat is at top my list of triggers.

Nothing easy about any of this.

Back in 1985 the authors of the CEBV Syndrome, Dr James Jones and Dr Stephen Straus told us in Incline Village that "patients with the EBV have allergies"

At that time "allergies" included chemical reactivity and they were fully aware of reactions to fragrances, paints, dry cleaning chemicals, etc. so they weren't talking about pollen and cat dander.

"Allergies" undoubtedly meant the same thing as MCAS.

Strangely, everyone I knew with the Incline Village Mystery Disease had an "allergy to mold"

But it was not like a sneezy, coughing hay-fever type of allergy. It was a poisonous toxic chemical reactivity type of allergy. We soon learned that molds produce chemicals: "Mycotoxins" and this is what we were reacting to. We attempted to convey this to Dr Straus, Jones and many others but at this time, "toxic mold" was not yet discovered so they did not believe us.

After "The Holmes 1988 CFS" was coined I contacted many clusters diagnosed with the new syndrome and they described the same bizarre reaction to mold.

CFS doctors never looked into this, so to this very day they have not made the connection. I see that a few MCAS doctors are talking about mold-toxins, although they too appear to be unaware that CFS was actually based on a toxic mold incident. Every day, more people diagnosed with CFS learn that what they have is a little understood obscure Mold Reactivity and benefit by a strategy of "mold avoidance"

I strongly suggest you research the history of mold and its relationship to CFS.