Myalgic encephalomyelitis, 1955-1990

Melvin Ramsay, the Royal Free Hospital outbreak, and the evolving understanding of ME.

“the victims of ME should no longer have to dread the verdict of, ‘All your tests are normal. Therefore there is nothing wrong with you’.” - Melvin Ramsay, 1986.

In July 1955 a nurse and a resident doctor at London’s Royal Free Hospital fell ill with a mystery illness. The illness spread rapidly among the medical staff, particularly the nurses, and within ten days the hospital was forced to close its doors. Over the next few months the illness would strike 287 medical staff, and just 12 patients. Most of those who fell ill were women, but this was to be expected - the hospital had a policy of preferentially hiring women doctors, so most of its medical staff were female.

Those doctors who didn’t fall ill meticulously recorded the progress of the illness. It began with flu-like symptoms, headaches, and mood changes. After a few days the patients developed sore throat, nausea and loss of appetite, vomiting and diarrhea, dizziness and pain. In the second or third week the illness worsened and new, neurological symptoms appeared: blurred vision, vertigo, tinnitus, involuntary eye movements, tingling or loss of sensation, muscle spasms and muscle weakness. The weakness could be so extreme that the patient became partly paralysed. Two people lost the ability to swallow, and had to be tube fed.

The muscle weakness and partial paralysis led the doctors to suspect that they might be dealing with polio, the devastating viral disease that left children paralysed and needing an iron lung to breathe for them. But tests of the patients’ spinal fluid failed to turn up any sign of poliovirus. The doctors were fairly sure the illness was caused by some type of virus because it spread rapidly from patient to patient, and they calculated that it had an incubation period of six to seven days. But, although they did every test they could think of, no virus was ever detected.

The hospital remained closed for a little over two months. No deaths were directly attributed to the illness, and most patients eventually recovered. The hospital reopened and life seemed to return to normal. But this was not the end of the story.

Looking back over old medical records, the doctors realised that the outbreak had not been an isolated event. They found records of several patients who had been treated at the hospital in the months leading up to the outbreak, who had the same unusual symptoms. A similar, though smaller outbreak had taken place in Cumbria, in the north-west of England, several months before the Royal Free outbreak. And, at around the same time the mystery illness was ripping through the London hospital, a cluster of similar cases were recorded in Durham, in the north-east.

The doctors searched the scientific literature for further reports of similar illnesses, and they were amazed to discover that similar outbreaks had occurred all over the world, with epidemics recorded in:

• Iceland in 1948 and 1949

• Adelaide, Australia from 1949 to 1951

• New York State in 1950

• Middlesex Hospital in London in 1952

• Coventry, England in 1953, and

• Durban, South Africa in 1955.

It was a medical mystery. Similar outbreaks had taken place all over the world, with the same perplexing symptoms turning up in patients on different continents. In each case the illness spread rapidly from person to person like a virus, but no sign of a virus was ever found.

As months passed, the most shocking aspect of the illness began to reveal itself: the victims didn’t die, but some of them didn’t recover, either. The majority did return to full health, but an unlucky few remained so ill that they became permanently disabled.

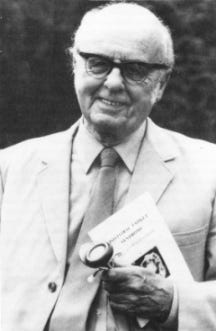

Dr Melvin Ramsay was the head of the Royal Free Hospital’s Infectious Diseases department at the time of the Royal Free outbreak. He developed an interest in the mystery illness which would stay with him for the rest of his life. Through the 1950s and 1960s Ramsay sought out cases of the illness, and compared notes with other doctors who were studying and treating it. He exchanged letters with doctors in the US, Australia and New Zealand. Many of those who developed the illness were doctors themselves, both in the UK and internationally.

In the years following the Royal Free outbreak the illness went through several names. It was called ‘Royal Free Disease’, then ‘encephalomyelitis’ then, ‘benign myalgic encephalomyelitis’, which was the name that stuck for a while. Melvin Ramsay fought for the word ‘benign’ to be removed. The disease was called ‘benign’ because the patients didn’t die, but, as Ramsay pointed out, it devastated people’s lives, leaving them unable to work or care for their families. The ‘benign’ was eventually removed.

‘Myalgic encephalomyelitis’ was (and still is) a controversial term. ‘Myalgic’ refers to the muscle pain experienced by those living with the illness - no-one has a problem with that part. ‘Encephalomyelitis’, on the other hand, means inflammation of the brain and spinal cord. Ramsay and his fellow doctors deduced that encephalomyelitis was present based on the neurological symptoms, and on the fact that the illness was associated with an infection. But at that time there was no experimental evidence of inflammation in the brain or spinal cord.

Early on, the name myalgic encephalomyelitis (or ME) referred to the acute, short-term infection that people developed, which lasted for a few weeks or a few months. Once it became clear that the illness had a chronic, long-term form, Ramsay called this chronic version of the illness ‘chronic ME’. However, since Ramsay’s time the terminology has changed somewhat. Today, when people talk about ME they always mean a chronic illness. In fact all modern definitions of ME require that the patient has been ill for at least three months.

Chronic ME was serious and disabling. Those with the mildest form of the illness could work, at least part-time, but many patients couldn’t work at all, and some couldn’t even care for themselves. Many were housebound or even bedbound. Nevertheless people didn’t die of it - unless you counted the rather high number of people who died by suicide.

Chronic ME had an unusually large number of symptoms, affecting various different parts of the body. Nevertheless, after years of carefully examining patients, comparing notes with other doctors, and poring over scientific reports, Ramsay found that it did follow a pattern which a knowledgeable clinician could recognise.

The key distinguishing feature of the illness was abnormal muscle fatigue following exercise. Ramsay wrote: “Following even a minimal degree of physical exertion there could be delays of between three and five days before muscle power was restored.”

Other muscle problems included: muscle pain, muscle spasming and twitching, and muscle weakness. Patients typically also had poor circulation, which showed itself as the patient having cold hands and feet, being pale or ashen, and being sensitive to temperature changes.

Then there were neurological problems, including:

• Cognitive problems such as word-finding difficulties

• Sensitivity to noise.

• Symptoms which suggested problems with the autonomic nervous system: frequent urination, excessive sweating, and orthostatic tachycardia

• “Emotional lability” or unusual mood changes. Ramsay mentioned “bouts of uncontrollable weeping” in normally stoic patients.

It was a feature of the disease that the symptoms fluctuated over the course of a day. (Many doctors simply couldn’t handle this - they felt that if a symptom existed at all, it should be there all the time, and always at the same level of severity. Then as now, many doctors believe that if a patient says their symptoms come and go it’s a sign that the patient is either a hypochondriac or simply lying. Ramsay was a rare doctor who was not afraid of complexity. He listened carefully to his patients’ descriptions of their experiences, and he saw that, despite the complexity, they painted remarkably similar pictures of what they were going through. And so he did perhaps the most powerful thing a doctor can do for patients suffering with a poorly-understood illness: he believed them.)

The only treatment for the illness was rest. Ramsay urged that those who were newly ill should rest as much as possible, and ideally take complete bed rest, as this would give them the best chance of recovery. He did recognise that this was not always possible, and he mentioned that mothers of small children found it particularly difficult to get the rest they needed. Exertion or excessive stress could prompt a relapse, as could further viral infections.

The evolution of the illness over time was impossible to predict. Some people made a full recovery, while others did not, and apart from the advice that rest promoted recovery it was difficult to see why one person got better while another remained ill. Ramsay estimated that any given person with ME had a 25% chance of still having it ten years later. Either things have changed, or Ramsay’s calculation was based on an unrepresentative sample of patients, because people with ME today have a far poorer prognosis.

ME was first recognised as a disease that appeared in epidemics, but there were also cases of people who developed it ‘out of nowhere’. In 1964 Ramsay worked with another doctor on a study of around 50 patients with ME who were not associated with any outbreak. He came to believe that ME was a mainly endemic disease - anyone could get it, anywhere, at any time.

There was further wrinkle to add to the picture. In the 1970s and 1980s, Ramsay began to encounter cases of people who developed chronic ME following infections with Eppstein-Barr virus or coxsackie B virus. Both of these viruses are very common and normally cause a mild illness. Eppstein-Barr virus causes glandular fever (also known as mononucleosis) and coxsackie normally causes a fever which passes after a few days. Yet it turned out both of these very ordinary infections could trigger ME in some people. Ramsay came to believe that chronic ME was not caused by the virus itself, but by the body’s immune response to it. Any infection could lead to ME, in a person whose immune system was in some way vulnerable.

Ramsay and his colleagues who shared his interest in ME wrote scientific papers, organised medical conferences, and did all they could to promote understanding of the condition within the medical community. As a result of their efforts many, though by no means all, British and European doctors developed some knowledge of the illness. ME was recognised by the World Health Organisation as a serious neurological condition in 1969.

Ramsay was less successful at convincing his American colleagues. The US did have some instances of ME, or an illness very much like it. For example, there was an outbreak in Punta Gorda, Florida in 1956. But the illness didn’t receive much recognition stateside, and the medical understanding of it was somewhat different. American doctors did not recognise the term ‘myalgic encephalomyelitis’, and instead called it ‘epidemic neurasthenia’, a name which implied that the illness might be psychological in nature.

In 1970 two British psychiatrists put forward a view of ME which was wildly different from Ramsay’s. They re-examined old reports of the Royal Free Disease and concluded that what had happened was not a viral outbreak at all, but an outbreak of hysteria. Their ‘evidence’ consisted in the fact that most of those who fell ill were women who lived in female-only housing. At that time it was believed that hysteria could affect both women and men, but it was much more common in women, and it was most likely to appear in women-only living spaces, such as convents and girls’ schools. In the sexist thinking of the 1970s, just the presence of men, with their superior rationality, was enough to stave off hysteria. Ramsay was dismayed by this paper, which he felt encouraged doctors to dismiss and disbelieve patients with ME.

Ramsay was horrified at the way those suffering with ME were treated by some of his medical colleagues. He met patients who were in “utter despair” because they had spent years seeing doctor after doctor and had endless tests done, but no-one could explain what was wrong with them. In his 1986 book, Ramsay mentioned a couple who divorced after several doctors declared one after the other that the wife’s ME was not real - she was simply neurotic. He mentioned a university student who developed ME and tragically died by suicide, and a woman who applied for incapacity benefit only to be told by a neurologist that she suffered from “near-delusional self-deception”. This neurologist believed that ME was “a figment of the imagination both on the part of the patients who think they are suffering from it and the doctors who make the diagnosis.”

Despite all Ramsay’s work, ME was only partly accepted in the world of medicine. It was not taught in medical schools or included in medical textbooks. It was a grey area: partly recognised, but not fully accepted.

Ramsay wrote his 1986 book ‘Myalgic encephalomyelitis and postviral fatigue states: the saga of the Royal Free disease’ to help other doctors understand the illness and give the best possible care to patients. Although there was no cure, Ramsay emphasised that receiving the correct diagnosis was of great benefit to patients, who had often been told for years that they suffered from depression or neurosis. In his experience, simply being told that the illness had a name and was not ‘all in the mind’ gave patients reassurance and hope. He wrote that patients should be advised to adapt to a slower pace of life and to get plenty of rest after any exertion. He recommended that patients attend local support groups, where people shared their experiences of living with ME, and where information about the disease was provided. In the pre-internet world, support groups must have been a lifeline for people living with a disease that most of the world did not believe existed.

In 1980 Ramsay helped found the ME Association, a charity which funds research, does advocacy work, and provides information and advice. He was active in this organisation until his death in 1990. There are two research funds in his name: the ME Association’s Ramsay Research Fund in the UK, and the Solve ME Initiative’s Ramsay Research Grant in the US.

References

Epidemiological aspects of an outbreak of encephalomyelitis at the Royal Free Hospital, London, in the summer of 1955, Nuala Crowley, Merran Nelson, and Sybille Stovin. J Hyg (Lond). 1957 Mar; 55(1): 102–122. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2217874/

Poskanzer CD, Henderson DA, Kunkle C, Kalter SS, Clement WB, Bond JO. Epidemic neuromyasthenia; an outbreak in Punta Gorda, Florida. N Engl J Med. 1957 Aug 22;257(8):356-64. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195708222570802. PMID: 13464939. Abstract available at https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM195708222570802

Acheson ED. The clinical syndrome variously called benign myalgic encephalomyelitis, Iceland disease and epidemic neuromyasthenia. Am J Med. 1959 Apr;26(4):569-95. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(59)90280-3. PMID: 13637100. Available at https://www.meresearch.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Acheson_AmJMed.pdf

McEvedy CP, Beard AW. Concept of benign myalgic encephalomyelitis. Br Med J. 1970 Jan 3;1(5687):11-5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5687.11. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1700895/

Ramsay AM. 'Epidemic neuromyasthenia' 1955-1978. Postgrad Med J. 1978 Nov;54(637):718-21. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.54.637.718. PMID: 746017; PMCID: PMC2425324. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2425324/

1988. UK. BBC Horizon - Monday 27th June. Episode title is ‘Believe M.E.’

Myalgic encephalomyelitis and postviral fatigue states: The saga of the Royal Free disease, 2nd ed. A. Melvin Ramsay. 1988. Available to purchase at https://meassociation.org.uk/product/saga-of-royal-free-disease/

Dr Melvin Ramsay Me generation champion. The Guardian, 9 May 1990. Available at https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-guardian-me-generation-champion/134260436/

VanElzakker MB, Brumfield SA, Lara Mejia PS. Neuroinflammation and Cytokines in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): A Critical Review of Research Methods. Front Neurol. 2019 Jan 10;9:1033. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01033. Erratum in: Front Neurol. 2019 Apr 02;10:316. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00316. Erratum in: Front Neurol. 2020 Sep 17;11:863. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00863. PMID: 30687207; PMCID: PMC6335565. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6335565/

Waters, F. G., McDonald, G. J., Banks, S., & Waters, R. A. (2020). Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) outbreaks can be modelled as an infectious disease: a mathematical reconsideration of the Royal Free Epidemic of 1955. Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior, 8(2), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/21641846.2020.1793058. Abstract available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21641846.2020.1793058

This post was edited on 30 July 2024 to fix some typos.

Thank you for pulling so much historical information into one place.

Such an important compilation. Thank you.

The disgraceful (corruptly manipulated and falsified data) PACE trial (Lancet 2011) was yet another attempt to demonstrate the ME was due to psychological flaws and/or laziness. Unfortunately it had widespread influence and has caused enormous harm to ME sufferers, their families, friends, and communities all around the world.